One of the most revolutionary changes in human philosophy might have occurred quietly over the last decade with you even hearing about it. A shift in the scientific community that ageing doesn’t have to be inevitable, that it is in fact a disease.

This may have something to do with the fact that we now know a lot more about ageing than at any point in history. We are closing in on why we age on a molecular level, and also, how we can use this knowledge to slow ageing, and how we may one day even be able to stop it.

The information theory of ageing

The most compelling understanding of why we age is known as the information theory of ageing. Very simply, we age because our bodies lose information over time.

Pretty much all life on Earth is subjected to epigenetic and genetic forces that manipulate how our genes are changed or expressed. But the two different forces store information about our DNA differently. Epigenetic information is stored in analogue format, and genetic data is stored in digital format.

Anyone with an analogue vinyl player knows that, although vinyl records sound great, they start to wear down after a while and the quality of the sound deteriorates. And it wasn’t long before vinyls were phased out by digital CDs which, if looked after correctly, can sound great forever.

This analogy also holds with the human body. Our epigenetic information is like a CD player reader. After a while, the theory suggests, the readers become so corrupted and broken that it cannot ‘read’ the CD properly — and so we deteriorate (age).

How our ‘longevity genes’ slow the ageing process

But in the information theory lies hope. Scientists are already familiar with at least seven so-called ‘longevity genes’ (in the technical jargon they are known as sirtuins). These longevity genes all have slightly different functions, but primarily they help to repair DNA.

We can think of longevity genes as kind of like first-response emergency teams, like fire fighters. Whenever the body is under stress, they rush out to put out the fires (amend breakages in the DNA). DNA that is repaired quickly and often slows the ageing process, because the ageing process is in part due to information corruptions, which rise as a result of mutations made either by mistakes in self-replication or by external influences.

Unfortunately, our longevity genes get overwhelmed by all of the DNA breakages, and in the end the fire burns down the house. We now have an idea how to help out our longevity genes, but first it is worth exploring how such a “first-response” system came about in the first place.

Repair or reproduce? — why ‘mild stress’ is good for the body

David Sinclair, the author of Lifespan, and Harvard’s leading age-researcher, believes that a primitive survival circuit developed in the earliest forms of life — and that all life has inherited that circuit and acts by it today.

The circuit is a very simple one with two modes: repair or reproduce. When the times are good and resources are plentiful, life ‘reproduces’. But when times are hard, all lifeforms enter ‘repair’ mode.

This may have had enormous survival advantages for the first single-celled life creatures that inherited it. Imagine, hypothetically, a primordial pool of single-celled life forms thriving in a pond billions of years ago. Except only one of them has evolved by chance the ‘repair’ function. The second a calamity hits, such as an intense dry season, all the cells that failed to hunker down would die.

So we can think of the ‘repair’ function as a state of emergency that calls our longevity genes — the fire fighters — into action. This is also the reason why it is good for the body to be a little stressed from time to time. In a time where we don’t have to worry much about food, and when we don’t necessarily have to exercise to catch our food, we don’t engage our longevity genes as much as we should do. Modern life has us almost always in the ‘reproduce’ mode.

Longevity now — how we can keep our longevity genes active

You can eat and workout in ways that put the body under mild stress, which calls our longevity genes into action. Note that mild stress involves short-term, easily manageable discomfort. For example, fasting puts the body under mild stress. That is good. But starvation and malnourishment is very bad.

One way to activate our longevity genes is to rely on plant-based meals only for our amino acids intake. Amino acids are plentiful enough in plants to keep us healthy and well, but they are superabundant in meat. By not eating meat and only eating plants, the body is cut off from an enormous intake of amino acids. This technique is called amino-fasting. If you eat meat, the chances are you already have too many amino acids in your system and could do with less. The plant-based diet will still provide you with what you need, but this drop in superabundance will be enough to shake the longevity genes into action.

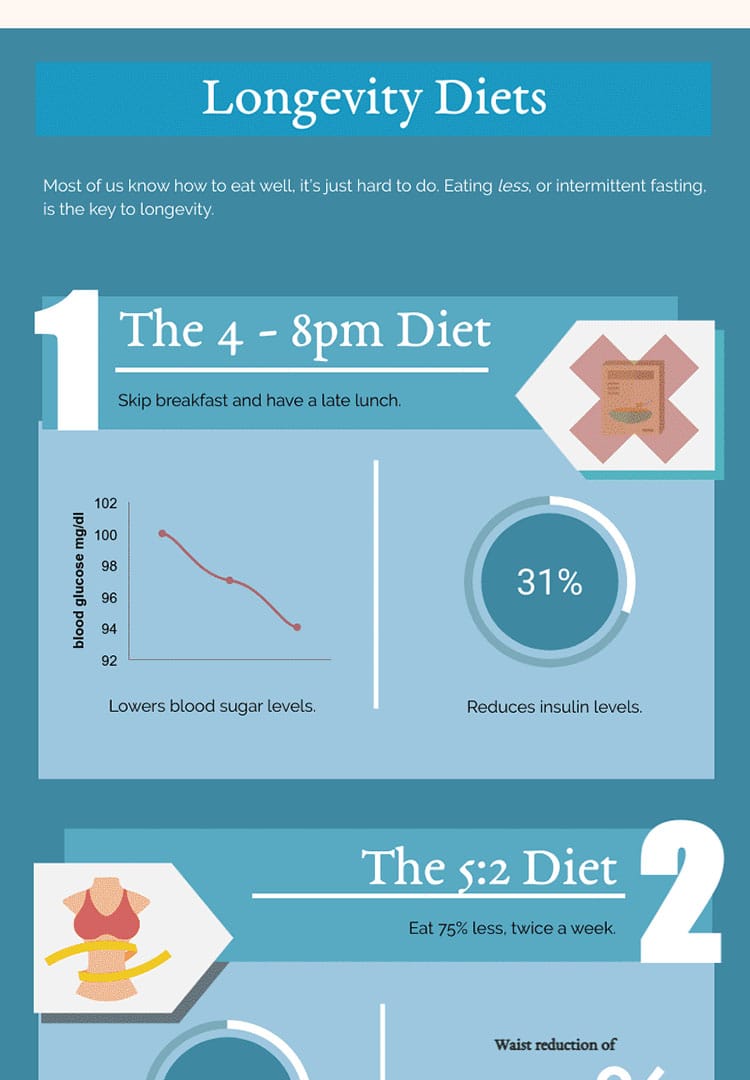

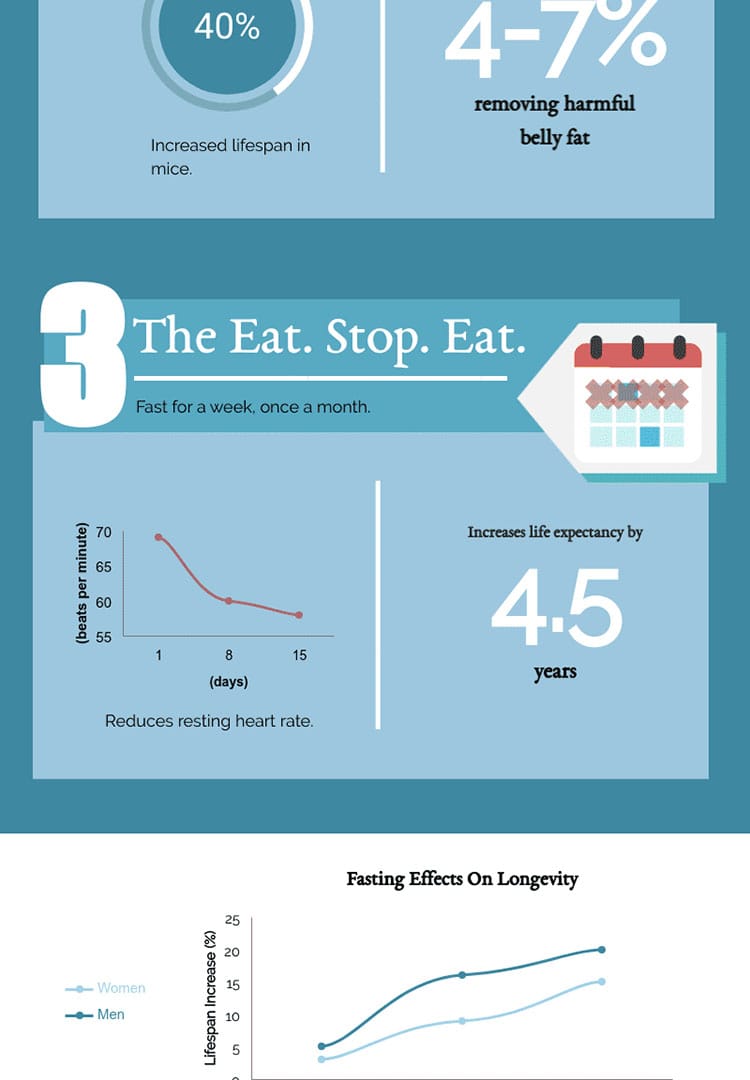

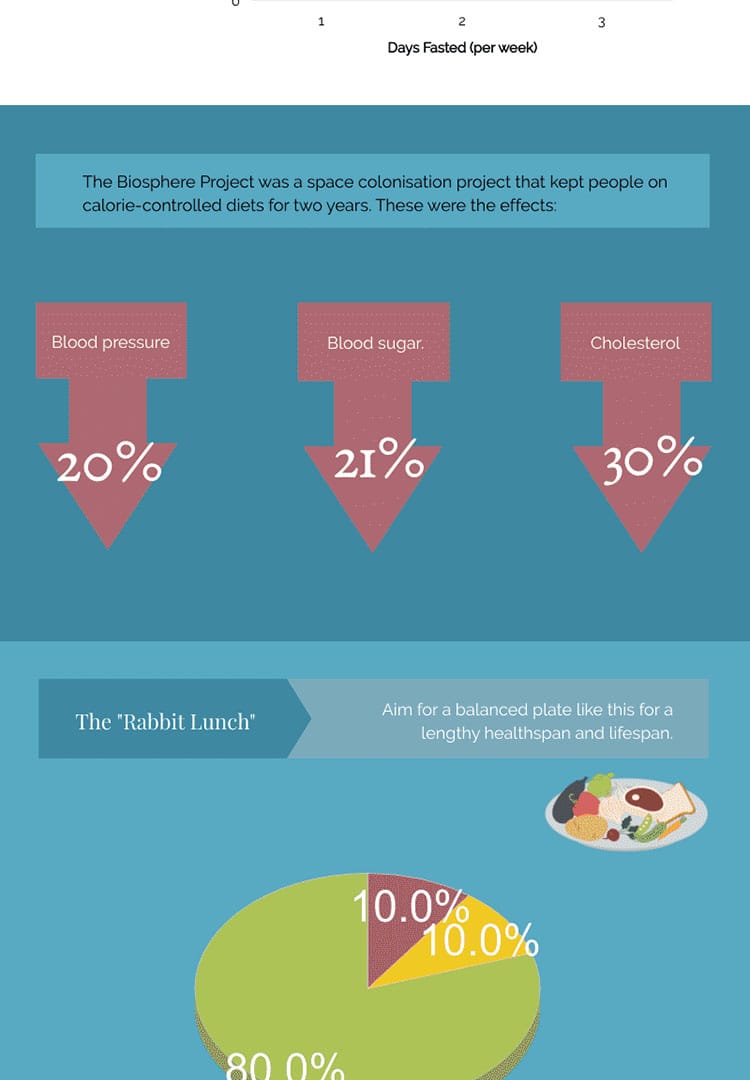

Fasting in general is brilliant for activating our longevity genes, and casually feeling hungry is good because it means the body is starting to worry about when the next meal will arrive. Of course, we know we can eat whenever we want. But the body doesn’t. The great thing about fasting is that it doesn’t have to be permanent or even that difficult. Some popular fasting diets only require a person to fast for two days of the week. Others, to miss breakfast and have a late lunch. There is also the added bonus that in the long run, fasting saves money on food purchases. People who regularly fast have lower blood pressure; sugar and cholesterol levels, and may even live up to 15 per cent longer than their non-fasting peers.

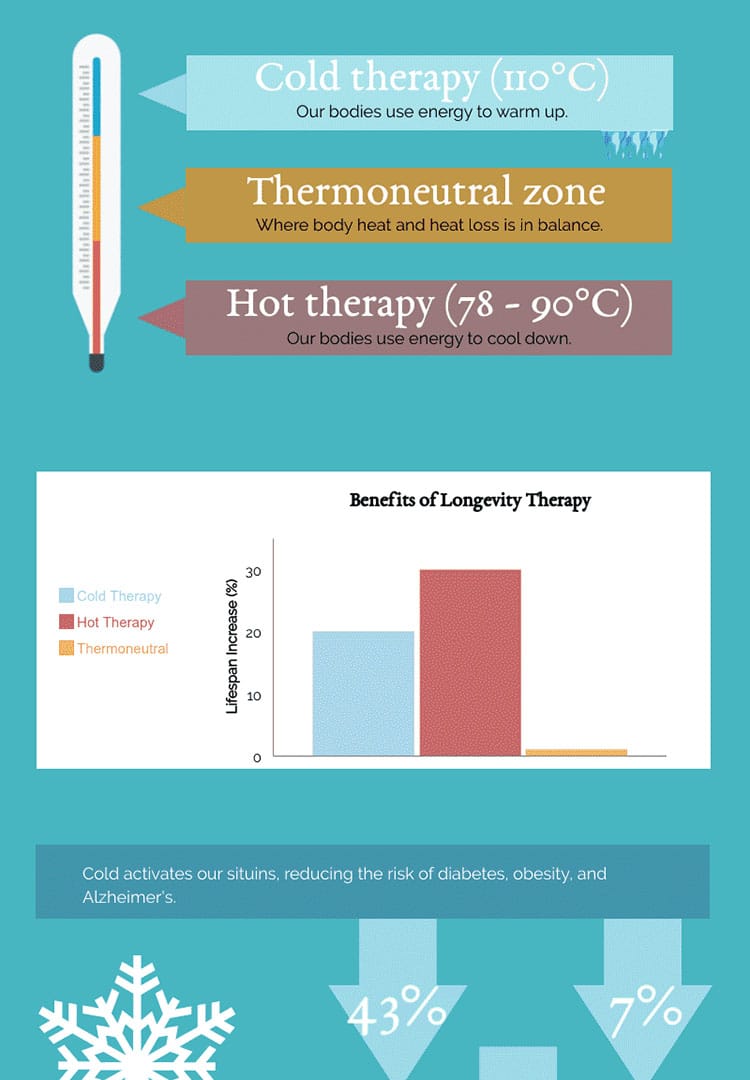

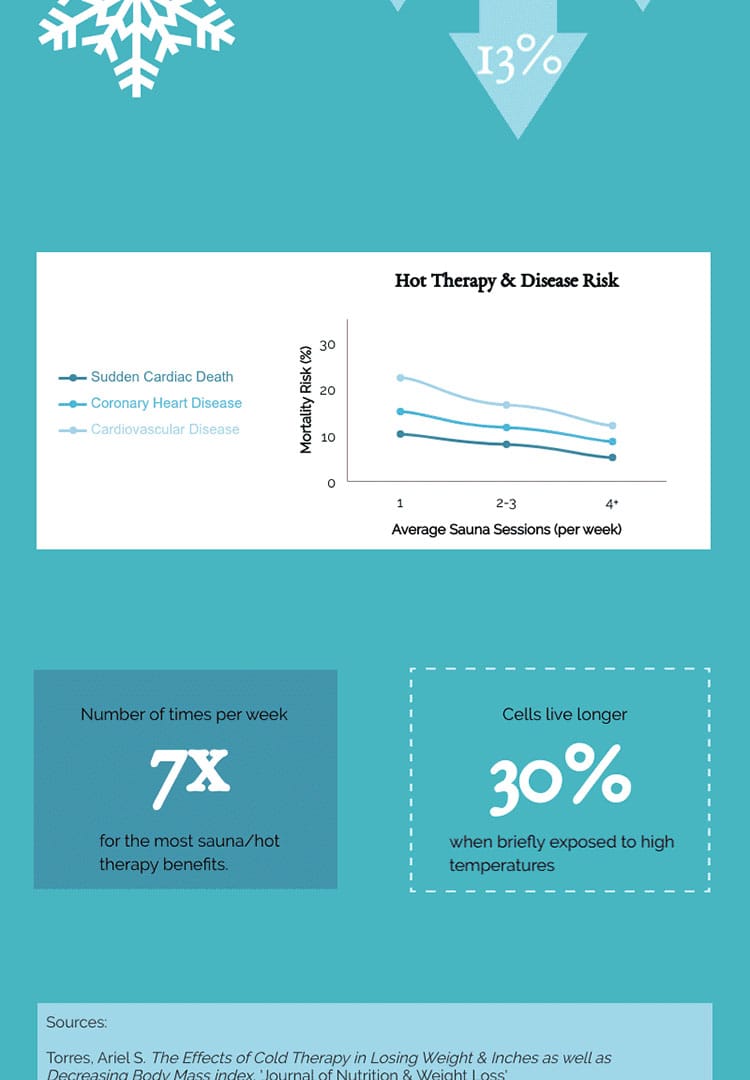

The extreme cold and heat also places stress on the body, and if we expose ourselves to such conditions for short periods of time, we put the body under a period of mild stress. A popular form of longevity therapy is cold bathing, you might be familiar with people who dunk themselves in icy cold water. But a similar effect can be gleaned from just walking briskly around the garden for 10 minutes on a cold day in just a t-shirt.

When we are too hot or too cold, our body gets stressed out, and has to use energy to restore our bodies to a thermoneutral setting. Similar longevity benefits play out in regular sauna takers, although there is less research on so-called hot therapy as there is for cold-therapy.

An exercise regime for longevity does not have to be particularly arduous or even time-consuming. It just has to stress out the body. The best type of exercise is high-intensity interval training. Where you push yourself as hard as possible for a short amount of time, for a few times.

High-intensity exercise triggers what’s known as the “hypoxic response” — a period of heavy sweating, shortness of breath, an elevated heart rate and deep breathing. The hypoxic response puts the body under a deep state of short-term mild stress. Which is perfect for activating our longevity genes. It is thought that a 30-minute run every day can add an extra decade on to one’s lifespan. Even 15 minutes a day has massive benefits.

Faking it — could medicine make us live longer?

An interesting analogy is to think of our longevity genes as lazy. In recent times, they have grown complacent like we have, and we need to give them a kick in order for them to work more efficiently.

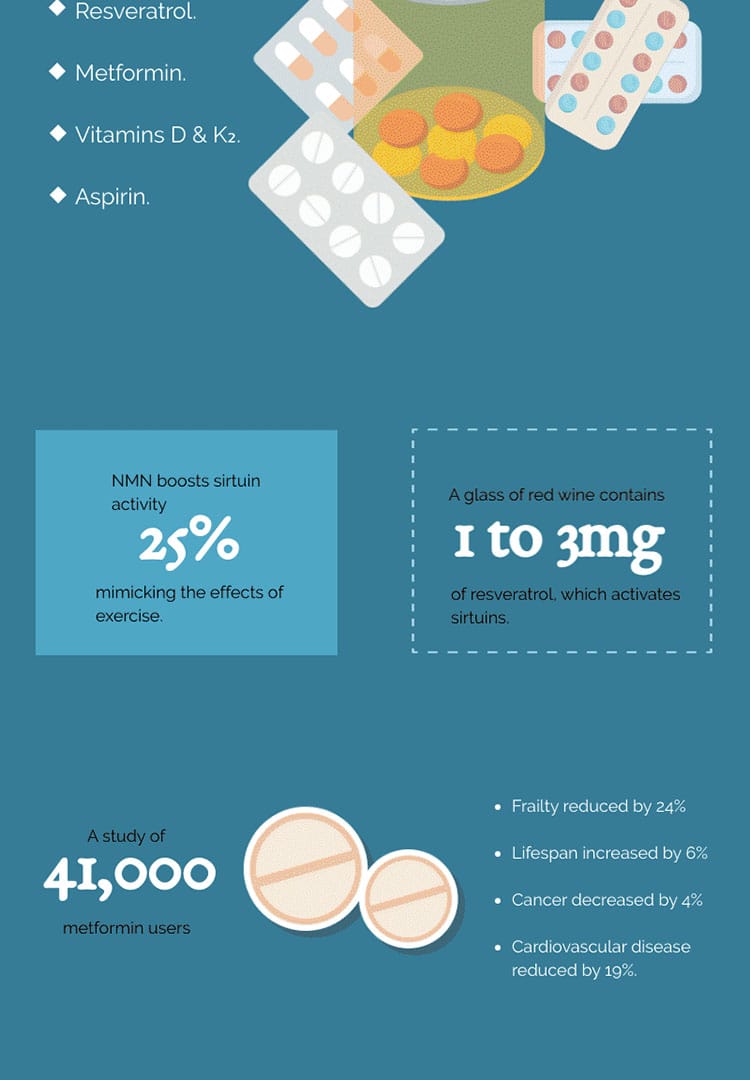

But if we are too lazy to motivate our lazy longevity genes, what then? There are a number of medicines and tablets already on the market that might help slow down the ageing process. Although because ageing is not yet classified as a disease, there is still a black hole of knowledge when it comes to clinical trials.

One promising drug however, looks to be metformin. This cheap drug has existed for decades and is used to treat diabetics. Studies of massive control groups have shown that metformin can mimic the stressful conditions we get from fasting or HIIT exercise, recruiting the longevity genes into action without us having even to do anything. Aspirin may also have enormous health benefits, along with Vitamins D and K2. But more research is needed.

Will we “cure” ageing one day?

David Sinclair said in his book Lifespan that a cure for ageing looks “easier than a cure for cancer”. He also went on to say that, because they were finding so much out about ageing, and how to treat it, and how there are hundreds of drugs that all look promising, he is looking forward to meeting his great-great-great-grandchildren.

So at least according to Sinclair, the answer is: almost certainly. And soon. For more information on the ethical dilemmas that curing ageing will present, read this fascinating journal entry, titled Tragedy and delight: the ethics of decelerated ageing.

Check out the infographic below for a visual recap of the themes discussed in this article.

Author: Neil Wright is a writer and researcher. He has an interest in science and the natural world, and has written extensively about longevity and health on his website.